CDFI Friendly America: Expanding The Reach of CDFIs

Comments prepared and presented by Mark Pinsky, CDFI Friendly America’s President/Founder, for the “Expanding Community Development Financial Institutions to New Geographies & Markets” event at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York on June 12th, 2025.

“

Thank you to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York for making it possible today to have this discussion about work that extends CDFIs’ reach. There is more for CDFIs to achieve and deliver, and that will require filling both geographic and product gaps in current CDFI coverage.

I appreciate the exceptional Community Affairs team here at the NY Fed. Thank you, David, Jonathan, Jacob, Carmi, and everyone else who brought us together.

And thanks to all of you for joining this conversation!

Since I started working in the CDFI industry in 1988, it has experienced several seismic shifts. The most significant was the formative two-step creation in 1994 of the CDFI Fund and the promulgation of new Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) rules in 1995.

After a great start under Democratic President Bill Clinton, the CDFI Fund’s future was in question following the election of Republican President George W. Bush in 2000.

The CDFI industry did two key things that transformed the field:

First, CDFIs learned to talk “Republican” and built a bipartisan base of congressional support that serves us well to this day.

Second, we turned a threat into a set of opportunities in 2003 with the “grow, change, or die” strategy that, among many outcomes, focused CDFIs on scaling the industry. It succeeded: The New York Fed reported almost two years ago that the industry had topped $450 billion in assets.

The housing crisis of 2008 and 2009, along with the resulting Great Recession, transformed how Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs) saw themselves. Equally important, it changed how the banking system, the banking regulatory system, Congress, state and local officials, and our local communities viewed CDFIs.

We [CDFIs] went from marginal and obscure to relevant and respected. As a result, CDFIs developed what I call institutional ego, the conviction that other people should believe our work is as important as we do.

In many places during COVID, CDFIs were the preferred financing channels for governors, mayors, and banks, as well as the federal government, proving that CDFIs are valuable because they are deeply trusted in and connected to the communities they serve. The racial uprising following the murder of George Floyd sparked a rededication of industry purpose—that is, aligning capital with social, economic, and political justice.

The Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund at the Environmental Protection Agency promises to add “environmental justice” to that list and to double down on the industry’s drive toward scale.

The current, turbulent discussion about federal regulatory, fiscal, and tax policies is causing seismic shifts right now for CDFIs and the people and places they exist to serve. My comments today are in that context: Expanding CDFIs’ geographic reach, or coverage, is an essential strategy for the industry's long-term sustainability, relevance, and efficacy.

The exceptional, enduring opportunity for the CDFI industry throughout its 40-year history is the potential to play a transformative role in a transactional business, to make structural and systemic changes in the systems that keep poor people poor … and rich people rich.

I do not have time today to discuss all the ways I think CDFIs have and have not made progress, but I want to note two things, one positive and one negative.

The positive is that the CDFI industry has caused fundamental changes in the ways governments and financial systems create opportunities for under-financed people and places. That is no small achievement, and we should take pride in what we have done.

The negative is that we have overlooked some of the structural and systemic flaws in our own industry that limit our efforts to leverage how government and the financial system work. Those flaws include the blind eye we turned for the past several decades to significant gaps in CDFI “coverage.”

Today, I want us to focus on the 30% of U.S. places—1,292 of them—that are CDFI “deserts.”

A CDFI Desert is any place in the U.S. with at least 10,000 people where at least 50% of the census tracts are economically distressed, and CDFI lending since 2005 is less than 80% of the per capita national average.

The national per capita average through 2022 is $714, and the 80% threshold is $571.

$714 is a number that, like any average, masks extreme differences. There are places in the U.S. with more than 10,000 people and high levels of economic distress that average more than $12,000 per person, and some that average in the single digits.

In CDFI Friendly America’s work, we are trying to leverage CDFI industry “scale” to create CDFI industry “scope”—truly national CDFI coverage.

CDFI Friendly America’s goal—with significant help and guidance from many others—is to grow an efficient, scalable system that reduces the number of CDFI deserts sharply over the next 20 years.

CDFI Friendly America’s theory of change is grounded in our belief that CDFI Deserts are, in fact, CDFI Opportunity Markets.

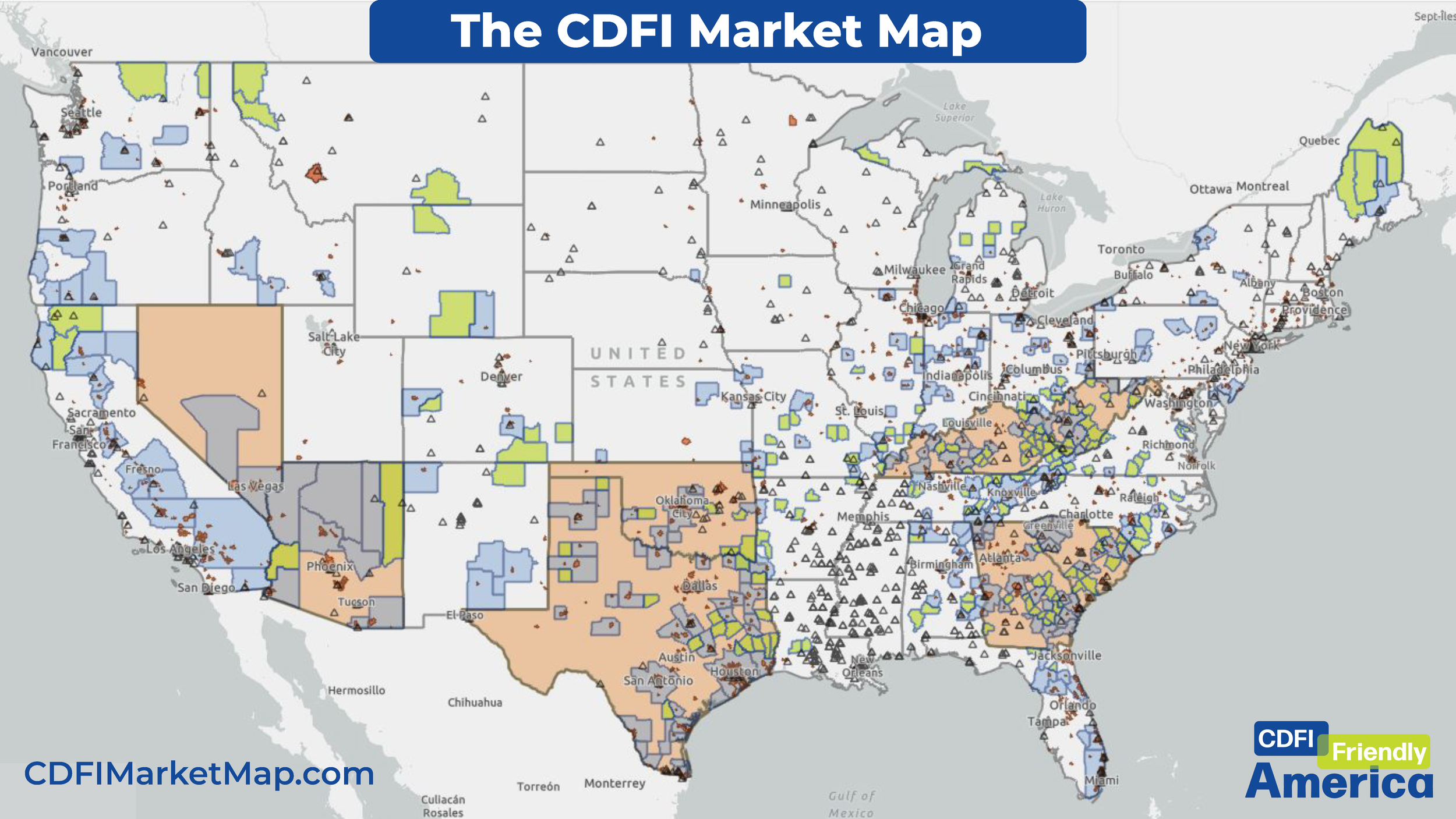

We wanted to show people what we were seeing in the data, so CDFI Friendly America created its CDFI Market Map. It’s free to use, and I hope you will explore it.

Today I’m going to spotlight some of the work we’ve done and some work we are planning to do. In the process, I’ll hype you up for our first panel.

You’ll hear from John Hamilton, the former Mayor of Bloomington, IN, and, in both an earlier career and his current one, a CDFI leader.

Working with Tina Peterson from the Community Foundation of Bloomington & Monroe County, the three of us co-created a way to bring CDFI financing there that is faster, cheaper, and more productive than any other alternative.

We ended up creating a CDFI Friendly development strategy there that we have used and, frankly, improved in four more places so far—South Bend, IN; Fort Worth, TX; the Evansville, IN, Region (including small parts of IL and KY), and Tulsa, OK.

You’ll also hear from Scranton, PA, Mayor Paige Gebhardt Cognetti, who invited us to work across multiple cities and a large rural area of Northeast Pennsylvania, or NEPA.

NEPA is different than other places that have made themselves CDFI Friendly. The three core cities—all within 40 miles—are demographically, economically, and politically distinct from one another. The rural areas surrounding the cities are different in other ways, particularly in their attitudes about the role of government.

We will hear multiple perspectives on CDFI Friendly communities from that panel of practitioners.

As a backdrop, I want to frame your understanding of the significance of CDFI Deserts as CDFI Opportunity Markets.

First of all, CDFI Opportunity Markets are observable at multiple geographic levels, based on census tracts.

I already told you that there are 1,292 CDFI Opportunity Markets at the “place” level.

At the County level, there are 853 CDFI Opportunity Markets, 34% of all U.S. counties.

At the Metro Area level, there are 310, 33% of all metro areas.

At the level of States & Territories, there are 9 Opportunity Markets, 17% of all States & Territories.

This has significant policy implications. In part, it explains why I used to get called up to Capital Hill regularly to explain to Senators and Congresspeople why they should support the CDFI Fund when they were not seeing CDFIs working in their states and districts. And it suggests how CDFI Friendly strategies can strengthen and sustain public support for the CDFI Fund and for CDFIs generally for economic reasons.

You should know that, since 2005, CDFIs have made loans in 100% of Congressional Districts—and so 100% of U.S. States and Territories. Only 20% of Congressional Districts are CDFI Deserts.

The three states with the highest per capita lending were—from largest to smallest—Mississippi, Louisiana, and New Mexico. The lowest three were—again from largest to smallest—Indiana, West Virginia, and Wyoming.

And here’s a data point that might surprise you: 65% of the $243+ billion in CDFI financing from 2005-2022 went to states that voted for President Donald Trump in 2024.

In short, CDFI lending is a winning, bipartisan policy idea just as it is a winning economic idea and an effective social justice strategy.

Before I wrap up, I want to offer a few observations explaining the importance of extending CDFI reach.

When we first started in Bloomington in 2017, John Hamilton and I sat down with about 15 CDFI CEOs to ask whether they would come to Bloomington if we made it CDFI Friendly. We were pleased that every one of them said “yes” after just a slight hesitation.

Now, 5 CDFI Friendly places later, we know with confidence that CDFIs will work in CDFI Friendly communities, for five reasons.

First, national, super-regional, and regional CDFIs are on the rise, they are eager to lend everywhere they can, and they like what we offer them.

Second, lending in CDFI Friendly markets costs less than it does in places where CDFIs have to house staff and acquire their own customers. As a result, CDFI Friendly loans can generate bigger spreads without burdening borrowers. This alone should drive CDFIs to rethink how they work… if we are able to develop enough CDFI Friendly markets.

Third, the intrinsic risk of place-based lending is geographic concentration risk and often—as was the case for Shorebank, for example—concentration of asset type within geographies. CDFI Friendly lending reduces those risks for CDFIs and CDFI investors.

Fourth, new geographies open new opportunities for increasing and diversifying capitalization for CDFIs that are concerned about sustaining asset growth.

Fifth, the 1,292 CDFI Desserts today are at least a $48 billion national CDFI Opportunity Market.

Investors and funders can leverage CDFI Opportunity Markets, too, by prioritizing CDFI lending in them with their investments. Indeed, a major bank we have been talking to is getting ready to do just that with an RFP it expects to release later this month.

The CDFI Fund could do the same. In its recent revisions of CDFI certification rules, the Fund encourages CDFIs to expand or extend their geographic reach by de-emphasizing strict adherence to pre-defined places.

This shift is happening across mainstream financial institutions, too. The soon-to-be-rescinded 2023 proposed CRA regulations boldly recommended—at the urging of the banks, I’m told—expanding CRA service areas for banks. While the proposal will be resorbed, the factors driving banks to want to serve expanded CRA footprints can and should support CDFI geographic expansions.

One last point:

In the wake of the Supreme Court’s 2023 ruling on Affirmative Action, the legal challenges filed against some CDFIs for prioritizing people and communities of color, and the broad federal repeal of diversity, equity, and inclusion strategies that we are experiencing right now. The data give us a reason for CDFIs expanding their reach.

In September 2024, CFA published a research paper titled “Place, Race & CDFI Lending.” We used CDFI Fund Qualified Investment Areas, or QIAs—to document in a new, highly pragmatic way, something we all know: There is a significant correlation between race and places of economic distress in most places.

To be a QIA, a geographic unit must have high poverty, unemployment, or county population loss, and/or low median family income.

What our finding means, though, might not be obvious. It means that CDFIs—which exist to serve historically under-financed, under-served, and under-valued people and places—can target communities of color in many, if not most, places based solely on economic distress indicators represented by QIAs. They can know down to the census tract level that their lending is disproportionately benefiting BIPOC people and communities.

There is a saying going around the CDFI industry today, in response to the pressure around racial injustice, to “change our words but not our work.”

In other words, CDFIs can and should once again turn another threat into yet another opportunity.

”

— Mark Pinsky